This is a segment from the Forward Guidance newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

For those who don’t know, I’m Canadian. However, I spent nearly every hour of the day thinking about macro from a US perspective. In the world of markets, the US is at the center and everything else is secondary.

Reflecting on the two worlds I live in poses an interesting vignette as to why it feels like the Fed keeps stopping and starting on its approach to monetary policy with respect to the economy.

The Canadian unemployment rate just hit a cycle high of 6.8% and looks to be climbing even higher, whereas the US’s unemployment rate seems to be flatlining. Yes, both economies were affected by an increase in labor supply caused by immigration, but the Canadian labor market is worse across the board.

Canada has managed to get its inflation rate back to 2% on a year-over-year basis, while the US remains stubbornly above target:

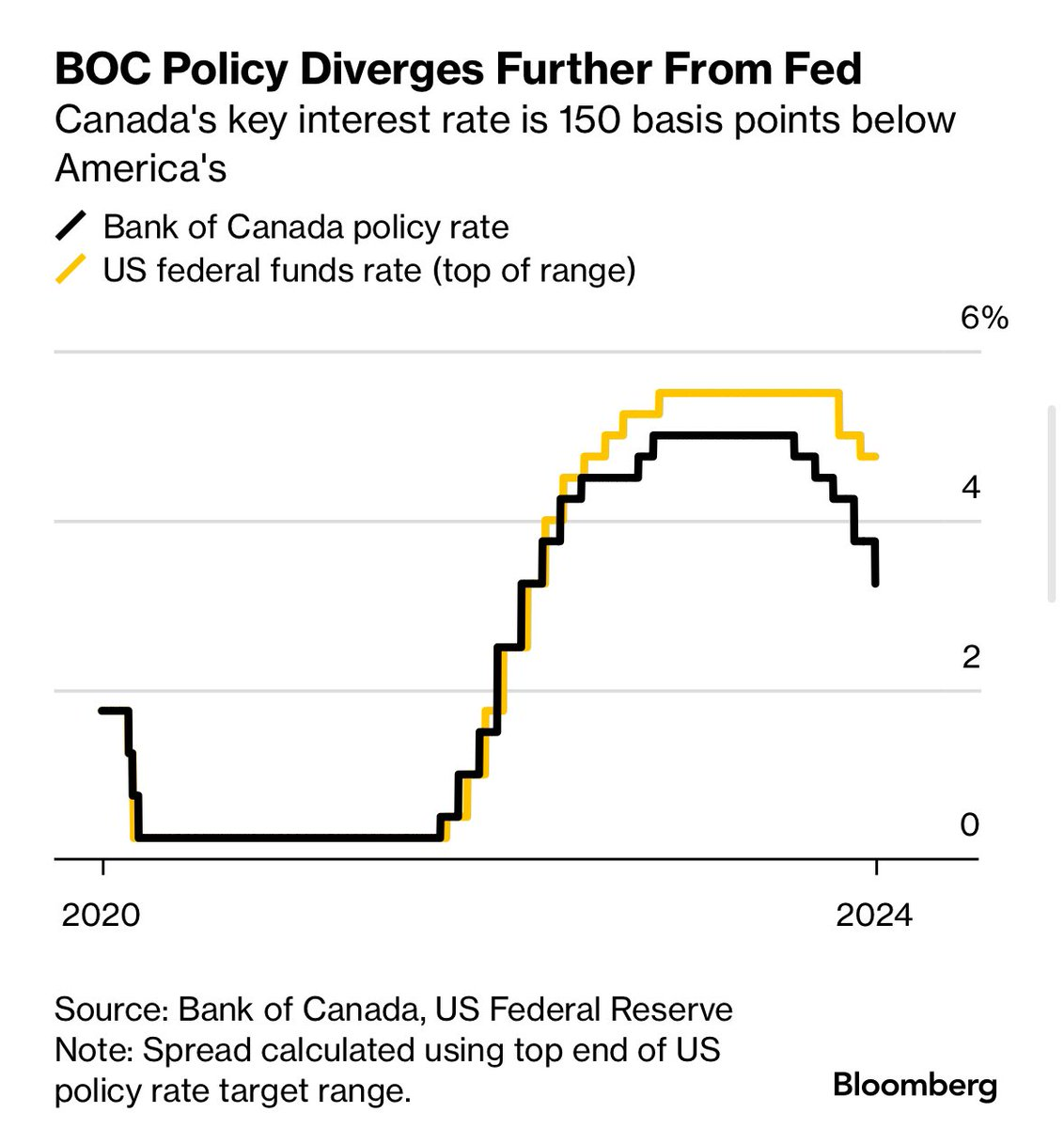

The Bank of Canada just surprised markets this week by going for another 50-basis point rate cut vs. the recent 25bps cuts they’ve been doing. The US is expected to squeeze in one more rate cut next week before pausing for a while as the economy continues to surprise to the upside.

So what gives? What’s driving the discrepancy between two similar economies that trade quite closely?

Simply put, the US financial system is much less sensitive to changes in short-term interest rates than Canada’s. Here are two examples:

Corporations

US companies have access to the largest debt markets in the world and can issue fixed-rate bonds at tight spreads, whereas Canadian companies (as is normal in non-US countries) are more inclined to issue floating-rate debt, which changes instantly with changes in central bank policy rate.

Households

In the US, homeowners can sit on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and as long as they don’t move, the Fed could hike rates to 50% and it still wouldn’t affect them. The rate they’ve locked in is the one for the entire mortgage. Considering how many households refinanced their mortgages at the Covid lows (sub-3%), as long as they don’t move, they’re unabated by increasing interest rates. This is very different in Canada and most other countries, where even on a 25-year fixed-rate mortgage, the rate gets reset every five years. Therefore, even if homeowners stay put, they will eventually be affected by the increase in rates.

These two examples showcase why the Fed is having so much trouble getting into a consistent policy path — its main tool cannot impact large swaths of the economy like it can in other countries. And so here we are instead, with increasing dispersion in economies between the US and everybody else. Oh, sweet US exceptionalism.